Decades ago, when I lived in Paris, I was told to catch the train to Chartres in time for the two English tours given each day at the Cathedral. Leaving from Gare Montparnasse, the suburban train is a bit of a milk run. But, I got there just before the Noon talk. I was fascinated by the cathedral and the speaker, Malcolm Miller. After scarfing down a baguette sandwich, I went back for the 2pm companion tour. My experience of entering any church, humble or monumental, Christian or not, was completely transformed from that day forward.

I doubt if Malcolm is still giving tours. However, his paperback guidebook, Chartres Cathedral, is almost as good. The cathedral is an amazing storyteller in its own right. Malcolm has been able to take the spectacular architecture, sculpture, and stained glass and to present the Medieval Christian literature and belief systems that it reflects.

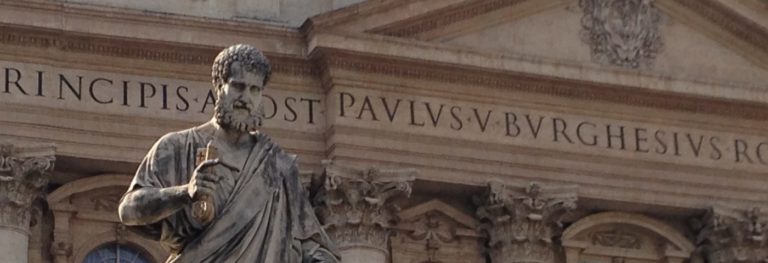

Following a fire in 1194 AD that destroyed the previous structure, the Chartres Cathedral was mostly reconstructed by 1223 AD. This is a relatively short period for such an undertaking and helps to explain why its iconography, particularly between the sculpture and the glass, is so unified. The church was a great big classroom in a world of intense illiteracy. You can almost imagine the young clerics using the stories and the lessons of the beautiful stained glass and the symbolic sculptures to teach lessons of everyday morality and intricate spirituality.

Miller recreates this with detailed explanations of most of the primary masterpieces. Christian ideology has been subject to interpretation since the crucifixion. A 13th Century cathedral is no different. The teachings of the walls and windows were intended to convey selected perspectives and to reinforce the essential role of the Christian church with the potential salvation of each of its visitors.

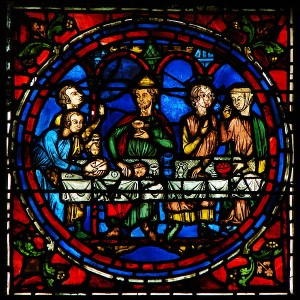

As an example of the depth of Miller’s insights, here is a quote from his discussion of one pane in the “Passion and Resurrection” window:

“Grief-stricken, Mary to her Son’s right and John the Apostle to His left contemplate Jesus upon the cross. Although the blood trickles from His five wounds, the closed eyes, the sideways tilt of His head and the limp body sagging at the hips all signify death. The wood of the cross, however, by virtue of the vivifying qualities of Christ’s blood, has become a living green bordered with red. A very popular anthem, known in the 12th Century, begins, “O crux, viride lignum”, for it was commonly believed that the “true” cross was made from the Tree of Life, which had grown in Paradise. Thus, of the two trees of the Garden of Eden, one brought about death, and the other, life.”

The symbolism of the artwork throughout the church seems intense and complex to 21st Century visitors. However, to the medieval populace, these were stories they knew by heart from retelling. Miller does a wonderful job of linking literature, lessons, and artistry. Once you have been introduced to this type of learning, you will be far more observant the next time you walk into a church. Its chosen lessons will speak to you more clearly.

The Cathedral at Chartres is a unique experience waiting for you to explore. Read Malcolm Miller’s Chartres Cathedral before you visit. Carry it with you as you wander around and through the church. And if there is an English tour, take it!