The most widely published book in the English language, the King James Bible, was born in the midst of the greatest religious upheaval in the history of Western Europe. The tale is told by Adam Nicolson in God’s Secretaries: The Making of the King James Bible. The action of the book takes place with the arrival of James I to the throne of England in 1603. However, the context for this singular attempt at ecumenical harmony begins almost a century beforehand, with the second great cataclysm of the Christian Church. (The “Great Schism” of Rome and Constantinople in 1054 was the first.)

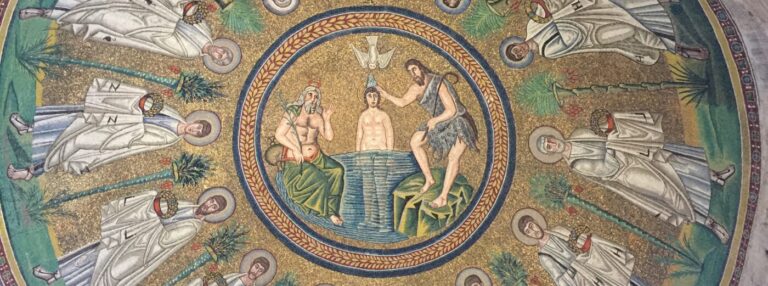

In 1517, a lowly Christian friar named Martin Luther became disgusted with the politics and personal shenanigans of the popes and bishops of the Roman church. He challenged them publically to clean up their act. When church leaders ordered him squashed like a bug, he went into hiding. Then he started publishing diatribes in vernacular German that declared the whole church structure of popes, bishops, opulent cathedrals, spiritual idols and symbols (like the cross), and the sale of salvation to be bunk. Luther claimed any good Christian could have his own relationship with God by following the Bible in the company of other good Christians.

In Continental Europe, the western church was wrenched apart and several shades of Protestantism were born. (See “The Christian Continent” in the Rhine/Danube River Cruise section.) This rupture set western European politics into a maelstrom of 131 years of war. (See “Sweden’s 15 minutes of Fame” in the Baltic Cruise section.) Scholars on both sides of the rupture began new translations of the Bible to suit their own perspectives.

In merry England, Henry VIII denounced Luther as a heretic and was declared “Defender of the Faith”, a title British monarchs still claim, though they no longer defend the faith for which they were named “Defender”. But, when Henry decided he wanted start his revolving door marriage policy, he was ex-communicated. Undeterred, Henry declared himself to be “Supreme Head of the Church of England”. The Anglican Church, or Church of England, was spun from sheer will power and the wave of a scepter. Henry was the only crowned head in Europe leading both his church and his state.

Henry’s ecclesiastical power play served up two hundred years of tumultuous British history including rebellions, revolutions, and restorations. Protestants, Catholics, and Anglicans all committed atrocities. The wounds have never healed and are evident today in “the Troubles” of Northern Ireland and the separatist movement in Scotland.

By 1603, Continental Europe was only on lap 86 of its 131 year war. England was suffering from the worst plague of its history. James I arrived from Protestant Scotland and was immediately set upon by English Protestant leaders who wanted him to a) eradicate the structure of Anglican bishops (left over from Roman Catholic days), b) remove unnecessary church symbolism (like the cross), and c) reorganize the church into locally administered congregations, called presbyteries. (Now you know where “Presbyterian” comes from.)

James had actually grown quite weary of Protestants in Scotland. He rather liked the idea of being the supreme leader of church and state. There was a whiff of anti-monarchical socialism and, perhaps, the seeds of revolution in the decentralized Presbyterian ideal. Kings prefer structure, hierarchy, and unquestioned obedience. So, James sent the Protestants packing and sided with the bishops.

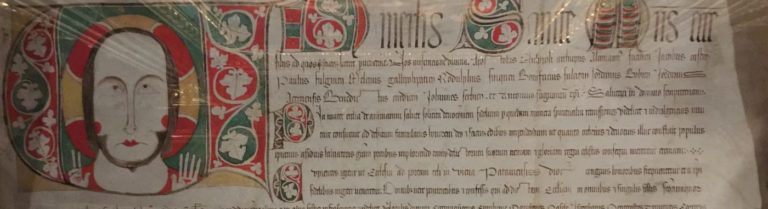

The Protestants made one request to which he agreed. They asked that the several different English translations of the Bible be replaced by an “official” Bible. They, of course, nominated their version, the “Geneva Bible”, translated in 1550 by very starch-collar Calvinists. James probably noted the 400+ references to “tyrant” and the distinctly anti-royalist bias. He preferred the 1568 Elizabethan translation called the “Bishop’s Bible” and its endorsement of spiritual leadership.

James took the opportunity to enlist several eminent scholars to review all current translations and to create an “official” version with the greatest hits from the older books. There was a vain hope that a new unified translation would resolve many of the religious differences throughout the British kingdoms and bring a unity to worship.

James charged his scholars to rewrite the Bible while relying heavily on the Bishop’s Bible. He wanted clean, understandable text that would support the Anglican Church structure. There were to be no references to “tyrants” or the Roman church.

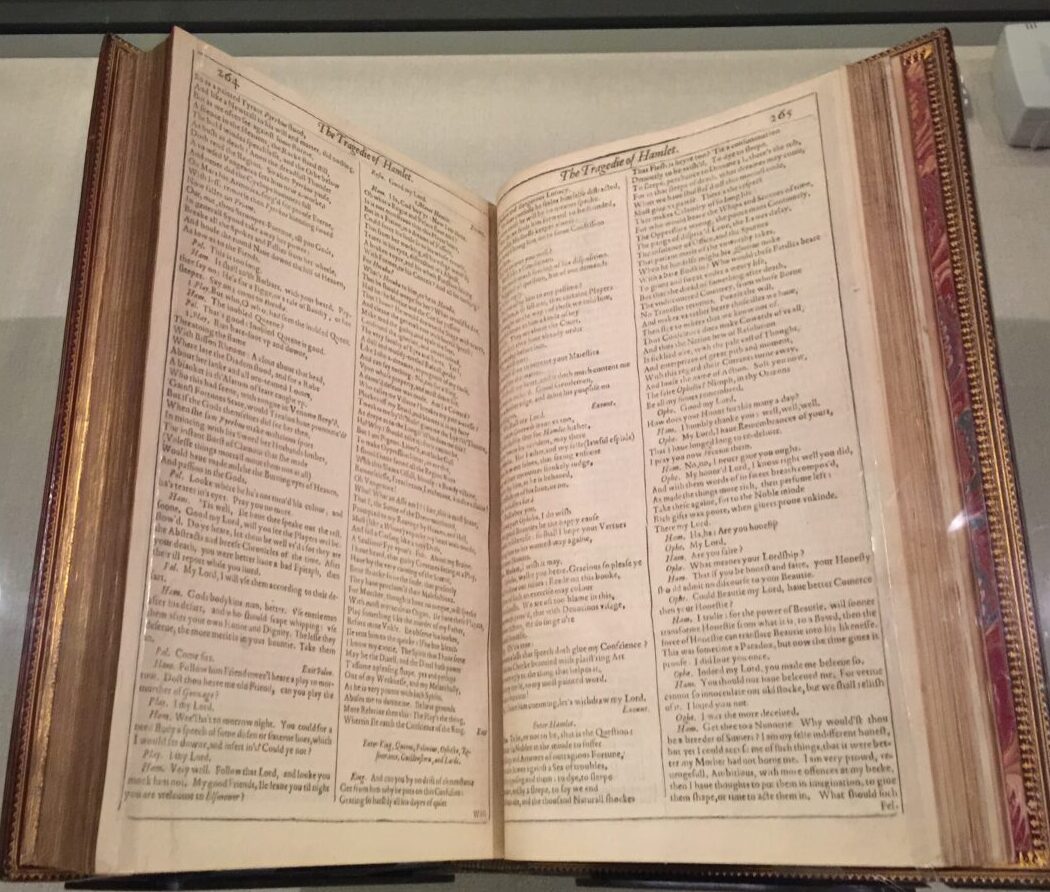

This was the time when William Shakespeare was writing his royal tragedies: King Lear, Othello, Hamlet, and MacBeth. The well-turned phrase was highly prized throughout England. It was a good time to set learned men to this singular task of composition. In the view of the author of God’s Secretaries: The Making of the King James Bible, Adam Nicholson, they succeeded: “That was their triumph: a polished collation, a refinement of a century’s translating, a book that became both rich and clear.”

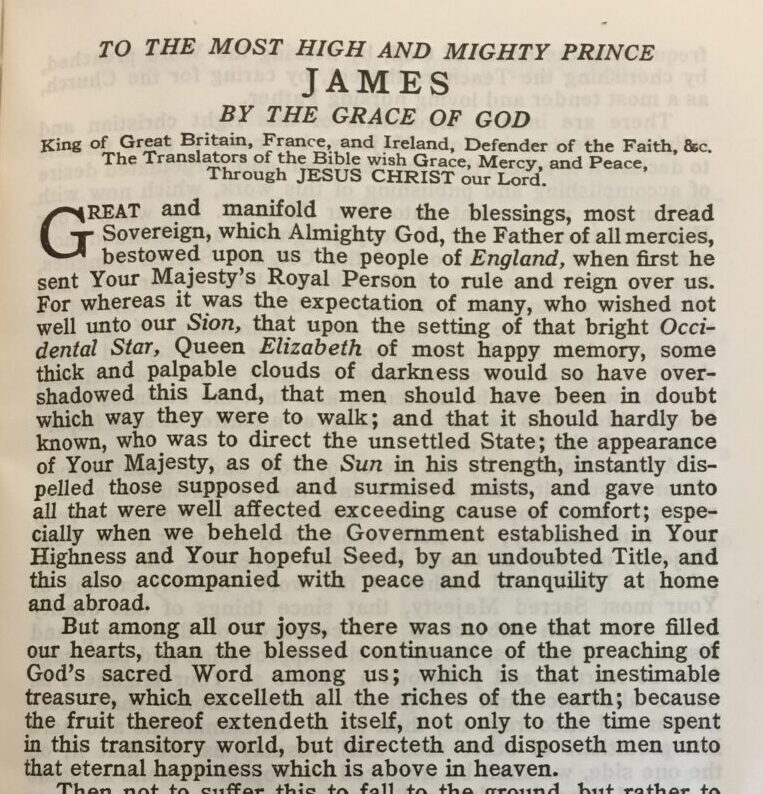

The scholars took seven years, to 1611, to complete their task. There is an over-the-top dedication to the King at the very beginning of the Bible. It took some time for the new translation to supplant all others throughout the English-speaking world. The King James translation was finally declared the official Bible of the Anglican Church in 1660. It is the primary text for Christian congregations throughout the United States. God’s Secretaries: The Making of the King James Bible is a great introduction to the historic events and tensions that helped shape the King James Bible.