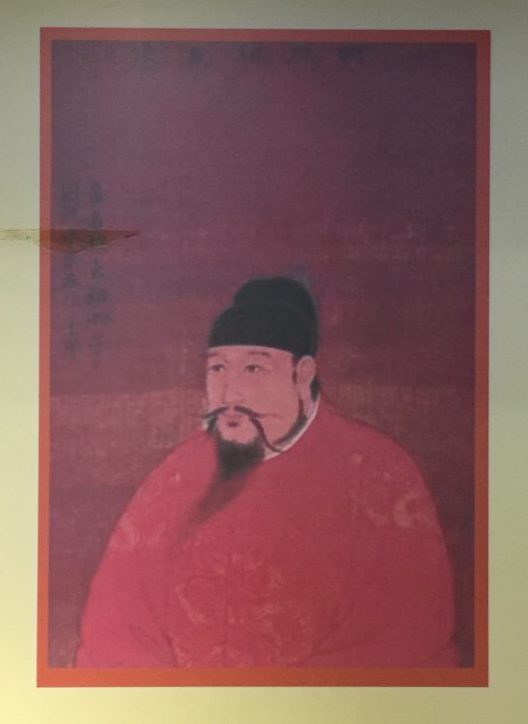

There is plenty of evidence that the Chinese, in the time of the Yongle Emperor of the Ming Dynasty, (Ming emperor number three), sent vast fleets around the world before the Europeans began their ambitious travels. He was looking to have envoys from around the world call on his court to acknowledge his eminence. One of the fleets did an extensive swing around Australia. In a fascinating book called 1421: The Year China Discovered America (P.S.), the achievements of these fleets, whose histories were wiped out by Ming emperor number four, are described.

The first Europeans arrived in Australia during the Age of Discovery. Willem Janszoon, a Dutch navigator based in Indonesia, sailed into the Gulf of Carpentaria in northern Australia in 1606. He assumed Australia was connected to New Guinea. Nothing came of his visits.

The intrepid British sailor, James Cook, charted much of the eastern coast of Australia during his first Pacific voyage in 1770. He sprinkled place names along the way, though in a rare show of English modesty, seldom his own. As mentioned above, he actually ran aground on the Great Barrier Reef. With the classic audacity of European explorers, Cook claimed the entire land for the British crown. (The Explorers: Stories of Discovery and Adventure from the Australian Frontier)

In May, 1787, Captain Arthur Phillip, (shown in the mural above), set sail for Australia with the First Fleet of 11 ships. They arrived in Sydney Cove on January 26, 1788, where they set up shop. Since then, January 26 is celebrated as Australian National Day. Of the 780 people who had sailed from Britain, 772 were petty convicts. The British continued to send convicts to Australia until 1848. A disproportionate number were Irish. In total, about 160,000 convicts were resettled from the Mother country. (The Fatal Shore: The Epic of Australia’s Founding, by Robert Hughes, and A Commonwealth of Thieves: The Improbable Birth of Australia

).

Twenty percent of the prisoners were women. This wasn’t exactly “Seven Brides for Seven Brothers”. These were tough women for tough men. They have an interesting set of stories, not all of which have happy endings. (The Tin Ticket: The Heroic Journey of Australia’s Convict Women)

From the moment the Europeans arrived in Sydney Cove, there were awkward relations with the aboriginal people in the area. In typical colonial fashion, the rights of these people were immediately dismissed. Though Phillip desired to have accommodating policies with the natives, there was no question what he would do if challenged. He showed tolerance, but he also ordered executions which his crew refused to carry out. Smallpox did more than its fair share of damage, just as it had done in the Americas. It would not be until 1992 that the Australian government would finally acknowledge the rights of land ownership for the aboriginal people. (Dancing with Strangers: Europeans and Australians at First Contact)

In 1931, the Australian government tried to relocate aboriginal children to schools that would raise them in a western fashion. It is not hard to imagine the damage a policy like this might have, though similar types of policies have been tried all around the world, including in America. One such personal memoir of this period is called Rabbit Proof Fence : A True Story.

From the first penal settlers in 1788, through its 19th Century history as a Crown Colony, there was no question that the residents of Australia were British. Aside from the aboriginal people and a few foreigners, everyone else knew they were a subject of the Queen. Of course, the folks still living in the British Isles had a somewhat lesser regard for their colonials. While that attitude had not served them well in America, it did persist, especially given the “convict” orientation for so many of Australia’s founding population.

In 1901, Australia was granted its complete independence as a “Dominion of the British Empire.” That basically meant that they ruled themselves through a Parliamentary system, with the British queen becoming the Australian Queen. Even then, there was still some cultural confusion. Citizens did not really know what it meant to be Australian. As Europe lapsed into World War I, a new sense of Australian identity came into focus with one galvanizing event: Gallipoli.

Most people probably do not know where Gallipoli is or was. It’s a peninsula in Turkey, on the northern shore of the Mediterranean entrance to the Dardenelles and the Bosporus Straits. These waterways have huge strategic military importance as the entrance to the Black Sea. In the early months of WWI, everyone chose sides, with Britain, France and Russia aligned against Germany, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the Ottoman Empire.

Winston Churchill, British First Lord of the Admiralty, devised a strategy whereby the Allied forces would assault and capture the Dardanelles/Bosporus waterway and Constantinople, all in one sweeping invasion. Then they would proceed to control the Black Sea where they could support the Russian Eastern Front against the Germans and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It looked great on paper.

The Invasion force included British troops and the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps, (ANZAC). This was the first time since Australian independence that any soldiers in a battle represented Australia and New Zealand. It was their very first combat mission. At the outset, it was apparent that the ANZAC troops were not as “regimental” as the British. They were far less concerned about a spit-and-polish image, or being told what to do. With their penal colony heritage, no one was sure how well they might perform under pressure. The British had no high expectations.

When the assault finally launched, the ANZAC troops were the vanguard. They were intrepid in the landing and the efforts to establish a position. The Turk defenders fought back valiantly and far more effectively than the Allies thought they would. After eight months of fighting, and enormous casualties on both sides, the Allies withdrew. The campaign had been a strategic failure.

In the heat of this treacherous and demanding arena, the ANZAC troops exceeded all expectations. Reports about the action attributed “bravery, ingenuity, endurance and comradeship” to the Aussies and Kiwis. They demonstrated that they supported each other extraordinarily well, inventing the concept of “mateship” and earning the nickname “digger” for their persistence. These all became qualities ascribed to Australians which, in combination with their irreverence and casual demeanor, became the new identity for the new country. There are a number of excellent books on the battle and its legacy, including: Trenching at Gallipoli; The Personal Narrative of a Newfoundlander With the Ill-Fated Dardanelles Expedition: Fated (Classic Reprint), Alan Moorehead’s classic, Gallipoli (Perennial Classics)

, and, for the Turkish perspective, GALLIPOLI: THE OTTOMAN CAMPAIGN

.