Though the Danes seemed well established in the Danelaw side of Britain in 877 CE, the Wessex royalty did not want to concede the match. The English fought back under Alfred the Great and his successors, retaking much of England by 955 CE. Two books tell this important story, Alfred the Great: The Man Who Made England and the most important source of the history of England for the First Millenium, The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

However, the persistent Danes kept up raids through the end of the Tenth Century. Hold that thought.

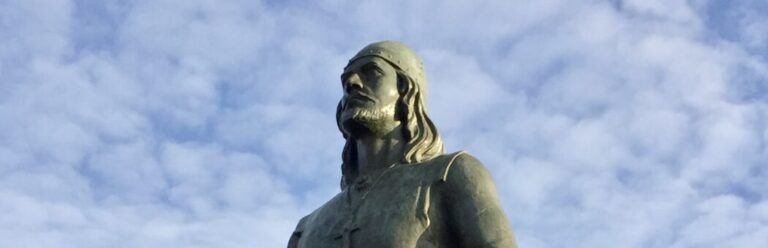

Meanwhile, across the English Channel, Rollo the Viking, following the example of his ancestor Ragnar, invaded northern France. French King Charles III “The Simple” signed a treaty with Rollo in 911 CE, granting him the Duchy of Normandy (Land of the North people), and promptly put him in charge of keeping any more Vikings from sailing up the Seine to Paris.

Rollo’s family became accustomed to French cooking and started to multiply. They even became the primary benefactors of the development of the Benedictine abbey at Mont St. Michel. Rollo’s grandson, Richard the Fearless, had a son, Richard II, and a daughter, Emma. Richard II’s grandson was a strapping lad named William. Destiny was about to shine on him. Pay attention to the daughter, Emma. She is the key to the rest of the story, in Queen Emma: A History of Power, Love, and Greed in 11th-Century England. Let’s get back to Britain…

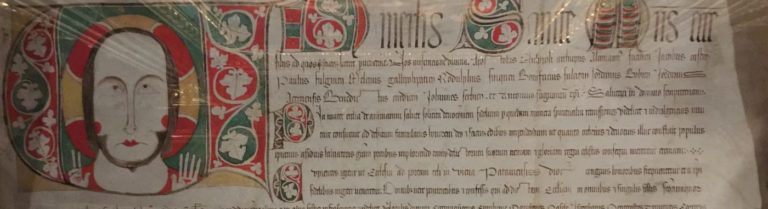

In 978 CE, Aethelred II, “The Unready”, was crowned King of Wessex, which was most of southwestern England. The story begins with Aethelred the Unready: The Ill-Counselled King It was a relatively prosperous time for Britain. But, the Danish raids persisted with increasing intensity. Aethelred attempted to pacify the Danes by paying lots of tribute, “Danegeld”, to the Danish invaders. But, money did not buy Danish happiness. Using Normandy as a base, they continued to attack all along the British coast.

Aethelred went so far as to travel to Normandy to negotiate an accommodation. In 1002 CE, he married winsome Emma, sister of Richard II, hoping family ties would solve the Viking problem. Unfortunately, Aethelred lost his cool when he returned to England and ordered the massacre of all Danes on British soil. Bad move. The Danes vowed revenge.

In 1013 CE, Danish King Swein Forkbeard invaded England and swept across the country. Aethelred was forced off the island and headed to Normandy, home of his Viking in-laws. Swein unexpectedly died in 1014, and the British nobles invited Aethelred back to rally Britain against the invaders. He was initially successful, until Swein’s son Cnut returned with a full Scandinavian force in 1016 CE.

Cnut defeated Aethelred and his son, Edmund, both of whom died, leaving all of Britain to Cnut. Though he already had a Danish wife and two sons, Cnut married ambitious Emma, Aethelred’s Norman Viking widow. Her two British sons, Alfred and Edward, were packed off to Normandy for safe-keeping. Cnut and Emma had a bouncing baby boy of their own, called Harthacnut. He was raised in Denmark for his safe-keeping.

The Viking raids stopped and peace reigned. After a good run, Cnut passed away in 1035 and the political ping-pong began again. This important turning point in British history is described in Cnut: England’s Viking King, and The Reign of Cnut: The King of England, Denmark and Norway (Studies in the Early History of Britain)

)

Seventeen year-old Harthacnut stayed in Denmark to defend his claim to that crown. As the only one of Cnut’s five sons and half-sons still in Britain, Harold Harefoot, Cnut’s second son by his Danish wife, was named regent. Persistent Queen Emma remained a strong rival presence, still hoping to preserve the throne for Harthacnut, or one of her other true sons.

Harold was finally crowned in 1037 CE, and he promptly sent the conniving Emma packing back to the continent. Harthacnut consolidated his Scandinavian position and prepared to lead an army to Britain just as Harold passed away in 1040 CE. Harthacnut landed, arm in arm with Mother Emma and assumed the role as King of Denmark and Britain. He was 22 years old, though evidently in ill health.

In 1041 CE, King Harthacnut invited his half-brother, Edward, (Emma’s son by Aethelred), back from Normandy. A year later, Harthacnut was dead and Edward, with the backing of Godwin, the powerful Earl of Wessex, was King of England. After two husbands and two sons, Emma was up to four kings of England. Though she passed away in 1052 CE, she wasn’t quite done.

Edward married Godwin’s daughter, Edith. No children, therefore, no heir. Meanwhile Edith’s four brothers all became earls, with Harold Godwinson, (Godwin’s son), taking the powerful Wessex chair. King Edward probably felt like General Custer, surrounded by suspicious in-laws. The relations between the Godwin’s and Edward were a little testy. The irony here was that they were Britons who should have felt some kinship in the face of all the Vikings.

In 1064 CE, Harold Godwinson, for reasons still debated by historians, was shipwrecked off the northern French coast and taken prisoner. He was bailed out by the nephew of his royal in-law. William, Duke of Normandy, at 36 years of age, personally extracted Harold from his dungeon and took him back to Normandy.

William wined and dined Harold. They fought some of William’s detractors in Brittany together. William knighted Harold and Harold swore to support William’s claim to the British throne, both of them noting that King Edward had no heirs.

The King passed away just after New Year’s, 1066. Whether or not he really rousted himself out of a coma on his deathbed and nominated Harold his heir, we will never know. However, the council of nobles, the Witenagemot, named Harold as King of England.

William was steamed and began preparations to defend his own claim to the throne. It must have made for interesting speculation among the English and Norman nobility. Choosing between Queen Edith’s brother and former Queen Emma’s grand-nephew is like trying to decide which of two poor poker hands should win the big pot. We suspect they voted pretty much along Wessex and Viking party lines.

William stalled on the French coast for most of the year. Then, he got really lucky. The gnarly king of Norway, Harald Hardrata, tired of his unsuccessful attempts to snag the Danish crown, turned his sites on Britain. His claim to the British throne was based on a supposed agreement made between Harthacnut and Harald’s Norwegian predecessor. Another weak poker hand. Without warning, the Norwegians swept down on unsuspecting northern England in September, 1066 CE. One of the Godwin brothers allied treasonously with the Vikings and early victories came easily.

Harold Godwinson had been poised in southern England to defend against the Norman invasion he knew was set to attack. He turned his forces to the north and soundly defeated the Norwegians. As if on cue, William finally weighed anchor, launching what would be the final assault of Viking descendants on Britain. Harold fought bravely, but lost. William was crowned King of England, Emma’s fifth contribution to British royalty. Five kings is a very strong poker hand. That’s how a Frenchman of Viking descent became King of England. It’s quite the story: William the Conqueror, by David Bates.

Three hundred years after the first assault on a defenseless monastery, the Viking era in Britain came to an end. By this time, all parties were church-going Christians. The Viking royalty in Britain and Denmark became more involved in mainstream European politics. The age of the marauding longboat was over.