The British used to proclaim proudly that, “The sun never sets on the British Empire!” Harrumph! After the discovery of the Americas and the expansion of maritime exploration, the European powers began three hundred years of colonialism throughout the rest of the world. When the smoke cleared, the British had elbowed the Spanish, French, Germans, Dutch, and Portuguese aside to amass a dominion over almost a quarter of the globe, even after those pesky thirteen colonies managed to secede.

There is an argument that could be raised that the British Empire was the single worst political misadventure known to man. It was built, in part, on gunboat diplomacy, slavery, apartheid, and opium. Its legacies include a) the mismanagement of Palestine and the Mid-East Crisis, b) the exploitation of India, resulting in the India-Pakistan rivalries, c) the Catholic and Protestant Irish “Troubles”, d) the occupation of Egypt, the Suez and the Sudan, e) the Chinese Opium Wars and the forced settlement of Hong Kong, f) the segregated societies of South Africa and Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), g) a group of impoverished Caribbean islands built on the backs of one of the most aggressive slavery operations in history, and h) the sloppy extractions from the colonial governments of Myanmar and Malaysia. It hasn’t been pretty. It won’t surprise you that the British have a different take on this: The Rise and Fall of the British Empire, and the even more defensive The Politically Incorrect Guide to the British Empire (The Politically Incorrect Guides)

.

The “success stories” of the British Empire include a) Australia, founded with 50 years of relocated criminals, b) New Zealand, colonized at the expense of the indigenous Maori people, and c)… Ta da!… Canada, …which was predominantly settled by the French! To this day, all three countries, though independent nations, voluntarily acknowledge Queen Elizabeth II of Britain as their monarch. Very curious!

Even more curious is the tradition that an explorer like Jacques Cartier could stand on the shore of the St. Lawrence River in 1534, the only Frenchman for 4,000 miles, and claim the whole unmarked, unmeasured territory in the name of the King of France. (The Voyages of Jacques Cartier) In 1682, Rene-Robert Cavalier, Sieur de La Salle, again, the only Frenchman for a couple thousand miles, stood on the banks of the Mississippi and claimed the whole watershed of the river for France. (La Salle: A Perilous Odyssey from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico

) That anyone, anywhere, took these guys seriously is astonishing. However, European arrogance being what it was, they did. Claims were acknowledged and then bartered in peace treaties like trinkets.

In between Cartier and La Salle, Samuel Champlain explored the St. Lawrence territories extensively until Louis XIII insisted he stay put and manage something. So, he founded Quebec and has been honored as the “Father of New France”, ever since. For that, he gets his mug in the mural on a wall in Quebec, (shown above).

The French were really the ones who let the big one get away. They had claimed and settled the Maritime Provinces (called “Acadia”), Quebec, and Louisiana. Together, this was an enormous swath of North America, from the Gulf of Mexico to Hudson Bay, from the Atlantic Ocean and the ridge line of the Appalachians across the Great Plains to the Rockies. Imagine how much better our cuisine would be today if they had only held on. We would never have invented TV dinners and fast food.

Unfortunately, in the Seven Years War, 1756-1763, which was basically a world war, the French and Spanish lost to the British. For a review of the worldwide contest, see The Global Seven Years War 1754-1763: Britain and France in a Great Power Contest (Modern Wars In Perspective). For a focus on North America and its implications for America, pick up Crucible of War: The Seven Years’ War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766

.

The British army “expelled” the French from Acadia. Then, the French ceded all of Quebec and the Louisiana lands east of the Mississippi to Britain in order to preserve their claim to the sugar plantations of Guadalupe and Martinique. Finally, they gave Spain the rest of Louisiana. What a misjudgment! Of course, Napoleon did win Louisiana back, only to sell it to Thomas Jefferson.

The last remaining vestiges of real France in North America are the two itsy bitsy islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon, just off the shores of Newfoundland. They were retained in the treaty to provide an anchorage for the French fishing fleet. So, for codfish and sugar, the French traded away some of the most lucrative real estate on the planet. That’s what happens when you lose wars.

So, now it was 1763, and the British controlled virtually all of North America east of the Mississippi except Dixie. They “rearranged” their colonies by a) restricting the thirteen southern colonies from expansion west of the Appalachian crest line, and b) reserving the lands west of the Appalachians for the Natives. In theory, they were attempting to avoid more Indian wars and curry some favor with the tribes. The French had always had better relations with the Natives than the American-Brits. In New France, they imposed British law and required an oath of allegiance to the British Crown. Thanks to these measures, British history was about to take a severe turn for the worse.

The folks in New France were, surprise, 99% French, who were, also, 100% Catholic. Aside from the fact that the British and French had been at war pretty steadily for several hundred years, the French settlers did not like losing their civil code of laws. More important, they refused to pledge allegiance to a monarch of the Protestant Church of England. Remember frisky King Henry VIII and his six wives? Excommunicated by the Pope! The French Catholic settlers were not happy.

What to do? It took a little time to sort this out. Finally, the British passed the Quebec Act of 1774. It announced the following accommodations:

- French civil law would prevail in New France.

- The elected colonial assembly was replaced by a Crown governor with a legislative “council”.

- Catholicism would be protected.

- Oaths of allegiance had the religious references removed.

- New France (Quebec) was extended south to Ohio, restoring the French and Indian relationships in the region south of the Great Lakes.

This helped pacify the French and the Natives. But, unfortunately, it had two very significant long term repercussions:

1) The firebrands in the thirteen restive southern colonies used these “anti-British” measures to add to their scorecard of oppressions, and

2) It set distinctions in place between Quebec and the rest of the Canadian Provinces that created the split personality of Canada that persists to this very day.

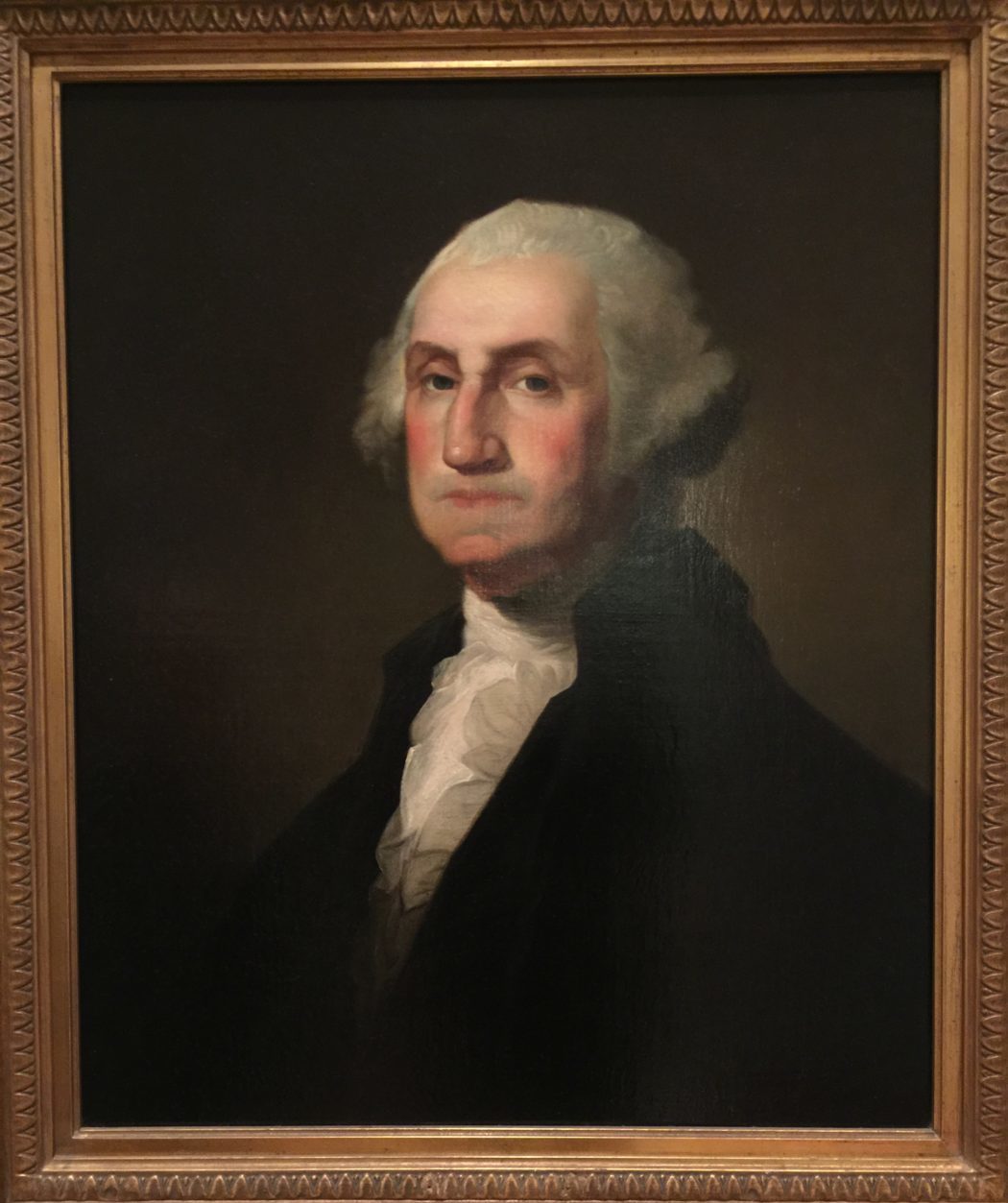

Almost exactly two years later, the Continental Congress of the Thirteen America Colonies slapped George III with the Declaration of Independence. See American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson, for a great discussion of Jefferson’s influences in writing the Declaration.

Grievance Number 20, (out of 27), used to justify this act of treason was:

For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies.

In other words, they objected to:

- The substitution of French Law for British Law

- The elimination of the representative colonial assembly

- the increased authority of the Crown’s governor

- The restriction of westward expansion imposed by the acts of 1763 and 1774

It’s not easy being King, or Emperor. George III could not please everybody. For a sympathetic take on his life and times: George III: A Personal History. It ultimately cost him the thirteen colonies and all of the western territory south of the Great Lakes. That’s what happens when you lose wars.