Spain plundered the gold mines of the Americas for almost three hundred years after Cortes took Tenochtitlan by force. In contrast, the Portuguese colony of Brazil was founded on sugar. Both 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus and Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies

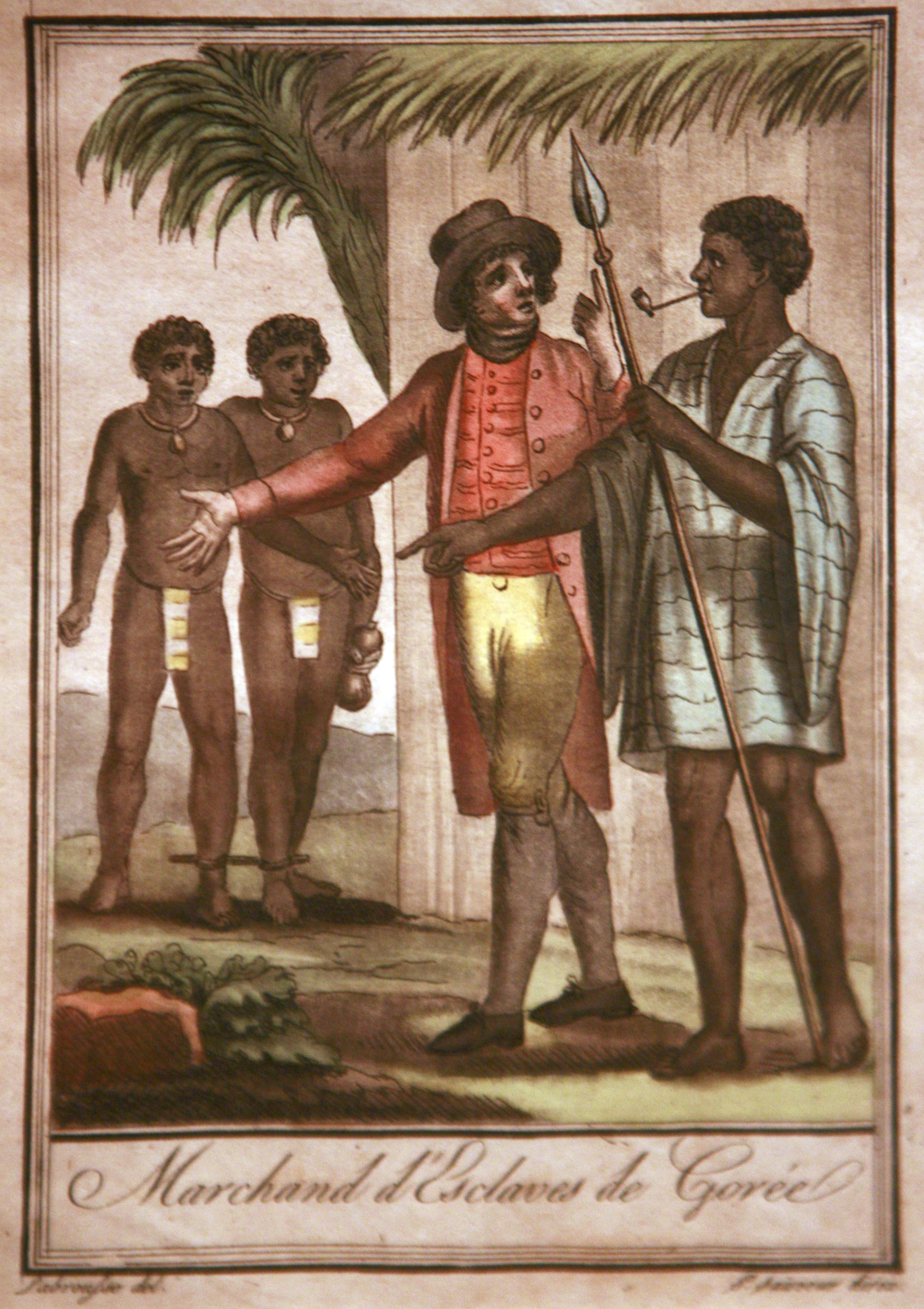

describe how the livestock brought to the Americas by the colonists carried smallpox, measles and other diseases that decimated the native Americans, both North and South. To fill the labor pool void, African slaves were imported. Europeans migrated looking for new opportunities and “mestizos” (mixed blood ancestry) were, quite literally, born.

The mongrel aspect of the South America population is illustrated by the estimates of mestizos in the major countries. For Brazil, Colombia and Venezuela, the multi-racial group is between 44 and 50%, while the European segment runs from 37 to 48%. In Argentina, there were no natives to mix with. So, they are 97% European. Only Peru maintains a significant percentage of native Americans, at 26%. African slave descendants account for 2-10% of the population, mostly in Brazil and Colombia.

One singular event triggered the end of the colonial period for most of South America and Mexico. Napoleon swept into Spain and Portugal in 1807. In the case of the Spanish American colonies, this meant that they had a new king. The contagion of liberal ideals wafted down from their North American colleagues. The advent of a French conqueror convinced many that the time had come for freedom from royalty. It proved quite the distraction for our erstwhile emperor, Napoleon’s Cursed War: Popular Resistance in the Spanish Peninsular War, 1808-1814

In 1813, young Venezuelan Simon Bolivar began to create rebellions in the northern colonies. In an unrelated development, Jose de San Martin began to lead his army of independence in Argentina. Bolivar, “El Libertador”, circled through Venezuela, Colombia, Panama, Ecuador and Northern Peru. San Martin took Argentina, then, crossed the Andes into Chile and north into Peru. On July 22, 1822, Bolivar and San Martin met in Ecuador. San Martin handed Bolivar the keys to the car and retired from the field. Bolivar mopped up Peru and then Bolivia. The Spanish colonies were gone. See Bolivar: American Liberator, and San Martin: Argentine Soldier, American Hero

Brazil took a much more unique path to its independence. When Napoleon arrived in 1807, the Portuguese court hailed the first ship out of Dodge and sailed for Brazil. They proceeded to declare their imperial court to be seated in the New World. All well and good until Napoleon had been shipped off, too. Then, the hometown Portuguese nobility and the rest of the crowns of Europe wanted the Portuguese to bring their throne back where it belonged. It was a collective effort, 1808: The Flight of the Emperor: How a Weak Prince, a Mad Queen, and the British Navy Tricked Napoleon and Changed the New World

By 1821, the political pressure forced the Queen and her prince regent to return to the homeland, leaving their son in charge of the Brazilian court. Within a year, the inevitable rebellion for independence took place, and even the young prince joined up. This was clearly a good move on his part, as he was named Emperor of Brazil and proceeded to rule for 58 more years. Only after he was gone did Brazil join the merry-go-round of Latin American coups and dictators.

The Latin American countries almost all took to independence awkwardly. Most revolutions and “republics” devolved into military dictatorships which continued well into the Twentieth Century. Pick any country and the chronicle of coups, assassinations, take-overs, and rebellions blurs with dizzying rapidity. This plague of political locusts was first satirized by the great story teller, O. Henry, who coined the phrase “banana republic” in Cabbages and Kings. His fictional portrayal of a Central American briar patch of scurrilous characters defined the everyday image of government south of the border.

During this long period of wandering in the dark, there are three figures, besides Bolivar and San Martin, who loom a bit larger than life in the annals of Latin politics: Mexico’s Santa Anna, Argentina’s Juan Peron, and Chile’s Salvador Allende.

Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón, parsimoniously known as “Santa Anna”, had a patronizing attitude as long as his name. His original success as a young Mexican general was to drive the Spanish from the Yucatan in 1821. From then until 1855, he navigated Mexico’s fickle political breezes, displaying a patrician’s distain for the common hombre.

Santa Anna was quite convinced the multitudes of Mexicans would always need the guiding hand of noblesse oblige. He was some version of ineffective president or dictator eleven times in the thirty-four year period during which Mexico’s leadership changed hands, sometimes quite abruptly, about every two years. For his staying power, if not his accomplishments, he is a central figure in the story of Mexican independence. The controversial assessment of his life is reflected in his biographies. The complimentary: Santa Anna of Mexico and the scathing: Santa Anna: A Curse Upon Mexico (Military Profiles)

A man of contradictions, Peron gave sanctuary to ranking Nazi refugees and then became the first Latin American government to recognize Israel and welcome Jewish immigration. A man of the people, he was not above crushing dissent. The man: Peron and the Enigmas of Argentina, and his wife: Evita: In My Own Words

, or Evita: The Real Life of Eva Peron

, and the hit movie: Evita

Not content to wrestle with his economic problems, Peron legalized divorce and prostitution in his Catholic country in 1954. He was practically excommunicated. There were just too many enemies for too many reasons and, by late 1955, he was fleeing the country while his opponents started dismantling his legacy. It was against the law to even mention his name.

In classic Latin American style, he rebounded from exile into the presidency in 1973 and started to reinstate his programs. He was gone a year later, leaving his Vice Presidential wife number 2, Isabel, to contend with a coup. It took until 2015 for Argentina to elect a non-socialist president. The experience has been so unsettling, they may reinstate the former socialist candidate who was convicted of corruption.

Just prior to Peron’s 1973 revival, a seasoned Marxist named Salvador Allende won the Chilean presidency with only 36% of the national vote in 1970. He launched into a classic program of nationalization of major industries, (Copper mining), social programs, and government spending. The stimulus looked promising for the first year. Then, the unflinching laws of economics caught up to him. Inflation took off, imports plunged, unrest began.

Of course, it didn’t help that the cold-blooded Nixon White House took extreme measures to reverse the fortunes of what they saw as a Communist encroachment in the Western Hemisphere. The US role in this episode is not praise-worthy. It took three years for the opposition, abetted by US interests, to stage the coup to take down Allende. After his ringing farewell broadcast, “Long live Chile! Long live the people! Long live the workers!”, he shot himself with an AK-47 given to him by Fidel Castro. Salvador Allende: A Revolutionary Legacy (Revolutionary Lives)

The age of political instability in Latin America is waning. There are still opportunities for larger than life personalities, like Hugo Chavez, to rally the oppressed. The divide between haves and have-nots is still wide, but the process is becoming less explosive. The future seems far brighter than the recent history.