As you are sipping your crisp Riesling while admiring the Rhine Valley from your verandah stateroom, you might be wondering how the Western European remnants of the Roman Empire morphed into the two major powers of modern Europe, France and Germany. It’s a tale about fathers and sons and the timeless tragedy of sibling rivalry.

We always hear that the Western Roman Empire fell to a flood of Germanic tribes. In this usage, the term “Germanic” appears to means “a bunch of unrelated groups of peoples migrating South and West from the amorphous, uncharted regions of north central Europe and Scandinavia for which there is no written historic record.” In other words, we don’t really know who these people were. They just showed up.

While Goths, Vandals, and Huns set their sights on sunny Italy and Spain, the Franks were content to settle the Rhine Valley. As the Roman legions withdrew, the Franks expanded west and then south, under the leadership of Clovis I, King of the Franks. The old Roman traditions began to die out. Clovis adopted the French language instead of Latin. Before France and Germany: The Creation and Transformation of the Merovingian World

His conversion to the Roman Christianity (all parts of the Holy Trinity are one and the same) helped him gain Papal support as he continued to attack other Germanic tribes in Burgundy whose Christianity was Arian (Jesus was the separate son of God). Then, he pushed the Visigoths back to Spain. For an historic moment, a glimpse of something resembling modern day France emerged for a brief time.

While assassination in the Senate may not be the optimum in succession planning, we can’t claim that Clovis’ Merovingian Dynasty improved much beyond that. Faced with his impending demise in 511 CE, Clovis elected to split his kingdom amongst his four male progeny. The thought was that they would all be equal, supportive allies. Silly Daddy! Siblings fell on each other pretty quickly.

Pieces of the original kingdom swapped back and forth. Heirs came and went, each splitting their particular slice among their own male heirs. Over time, the kingdom weakened by the dispersion of royal power. Each castle had its “Mayor of the Palace,” who was not royal, but who would actually run things. As the Merovingian power became diluted, it was inevitable that a strong mayor would arrive on the scene and shake things up.

In 687 CE, amidst an uprising of dukes, mayor Pepin II took charge of the two northern kingdoms of Austrasia, near Aachen, and Neustria, near Paris. His son, Charles Martel, added southern France by defeating the Muslim Moors at Tours in 732 CE, and preventing the conquest of Western Europe by Islam. With huge implications for the eventual culture of Western Europe and the Americas, the Muslims retreated to Spain and kept to themselves.

By 751, Martel’s son, Pepin the Short, had united the Merovingian lands, though he was still not royalty. He appealed to the Roman Pope, Stephen II, to grant him the throne in the place of the powerless scion of the crown. Stephan sized things up pretty quickly and decreed that he who had the power would do well to rule. Thus, Pepin became “rex Dei gratia,” king by the grace of God, not from inheritance. The line between royal and papal authority became ever more blurry.

This happened to be at a time of acute tension between the churches in Rome and Constantinople. The Roman Pope, Stephen II, was threatened by the northern Italian Lombards. Knowing he would get no help from Constantinople, and that Pepin owed him bigtime, an insecure Stephen traveled to Gaul and anointed Pepin as official protector of the church. By doing so, Stephen was overstepping his authority. Pepin trounced the Lombards and created the realm of the Papal States in the famous “Donation of Pepin” of 756 CE. By doing so, Pepin was overstepping his authority. The bond between Rome and France became tighter. The stage was set for greatness. The Carolingians : A Family Who Forged Europe

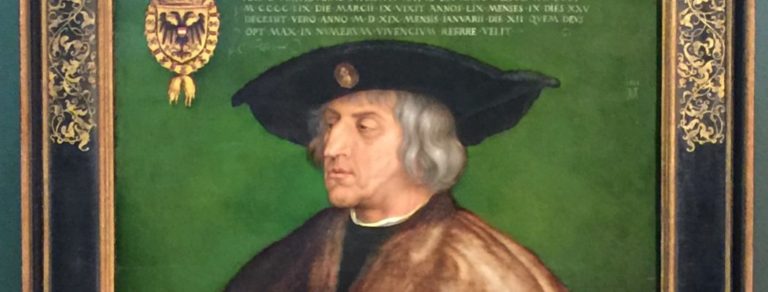

Charlemagne (Charles the Great) took the spotlight in 771 CE. He expanded the kingdom by conquest over much of modern day Germany, Austria, Hungary, and northern Italy. (See Altdorfer’s “Charlemagne’s Victory over the Avars at Regensberg”, above. Note the angel leading the golden warrior king.)

His home base was Aachen where he ran not only the kingdom but the Frankish Church. His exploits were recorded contemporaneously, by an admiring scholar in the king’s court, The Life of Charlemagne (Ann Arbor Paperbacks). Aside from his political achievements, he established a culture of learning to improve Latin literacy and knowledge of the classics.

In the tradition of Constantine and foreshadowing British King James, Charlemagne attempted to reconcile inconsistencies in the biblical narratives, with scholars producing a new version of the Scriptures. In order to improve the accessibility of these texts, the written language, which had been run-on sequences of letters, was presented for the first time with separate words, capital letters, and punctuation marks. Latin was the elevated language. French was the vernacular.

In 800 CE, Charlemagne was called upon to restore Pope Leo III to the Holy See, in spite of Leo’s questionable track record. Leo was so appreciative, he arranged to crown Charlemagne as the Holy Roman Emperor on Christmas day. Charlemagne (Vintage)

Well, we knew this party would end. Charlemagne passed away in 814 CE. Succession was not an issue as he had outlived all but one son. Unfortunately, his unimpressive heir, Louis the Pious, (the name Louis is a derivative of Clovis), rattled by a near fatal accident, attempted to partition the kingdom so he could devote himself to his faith. Noting the issues of the Merovingian succession, Louis tried to circumvent them with a version of primogeniture. One son was named Emperor, while the other three were to receive smaller kingdoms and be subservient. Silly Daddy! The four sons battled with each other and their father until Louis died in 840 CE. The sons fought among themselves for three more years.

Finally in 843 CE, the two remaining subservient brothers forced the emperor brother to partition the kingdom into three realms. The Treaty of Verdun created West Francia (much of modern day France), East Francia (much of modern-day Germany, Austria and Switzerland), and Middle Francia (a thin area running from the Netherlands through Burgundy to northern Italy). The middle kingdom would be the source of political tugs of war between East and West for the next eleven hundred years.

The fortunes and failures of future monarchies, alliances, feudal vassalages and evolving kingdoms would redraw the borders on this map a hundred times in the coming centuries. But the essential identification of France and “Germanic Europe” took shape out of these two formative periods in the adolescence of the political continent.