Historians like to use a term like “unite” in a sweeping phrase like “Charlemagne united the German tribes to complete the eastern expansion of his empire”. But, one has to wonder what exactly this meant. Did he invite them to tea? Did he throw a holiday barbeque? Was there a communal prayer session? No. Basically, it means he beat the tar out of them.

There are many instances in history where conquest is shown to be a short-term aggrandizement rather than a true nation-building exercise. German history would be just such an archetype. Check out A History of Germany in the Middle Ages. Beneath the cobbled veneer of Charlemagne’s East Francia, was a collection of Germanic tribes whose traditions and allegiances would forestall any true confederation until the Nineteenth Century. The original tribal divisions evolved into a set of territories referred to as the “Stem Duchies”. They included Franconia, Lorraine, Swabia, Bavaria, Saxony, and Frisia.

As the royal vigor of the East Francia Carolingians fizzled in 911 CE, the stem dukes, fearing a West Francian (French) claim of sovereignty, elected their own leader. This took a couple of rounds. Eventually the Duke of Saxony took charge, establishing what would become the Ottonian or Salian Dynasty. The Birth of the West: Rome, Germany, France, and the Creation of Europe in the Tenth Century

History also suggests that kings or queens with long tenures tend to have the biggest impact. It was 936 CE when dynastic namesake Otto I “the Great” started his 37-year tour of duty. He was a man of many accomplishments. At the same time, he set Germanic Europe on a collision course with the papacy that took four hundred years to unwind.

On the plus side of the ledger, Otto quashed the Magyar threats on his eastern borders with a finality that had eluded his predecessors. With Charlemagne as his role model, he established a cadre of learned scholars, founded abbeys, and supported literacy within his court. During his long reign, he was obligated to deal with a number of revolts, including his own son.

Around 950 CE, the title of Holy Roman Emperor was being volleyed listlessly between Eastern and Central Francians in southern France and northern Italy. An ambitious, mid-level noble usurper attempted to snatch the golden ring through treachery, poison, and forced marriage. The damsel in distress was beautiful, rich, very well connected, and desperate. She appealed to Otto with a marriage proposal of her own. Otto could see Italy in her eyes, crossed the mountains, won the day and got the girl. Now, he was King of Italy. His own ambition kicked in, as he could see himself as the inheritor of the reflected greatness of Charlemagne.

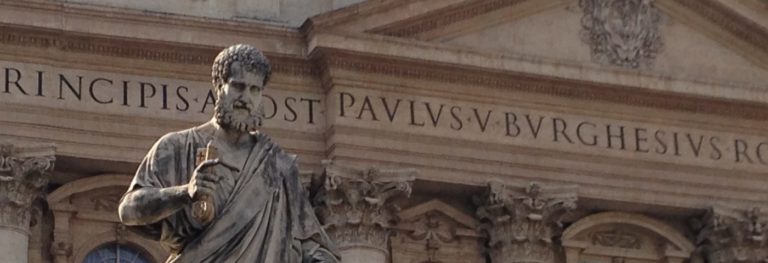

Otto’s second and third Italian campaigns, against the same usurper & son who had attacked Rome and were threatening Pope John XII, were historically momentous for two reasons. First, by combining the kingdoms of Italy, including Southern Italy and Sicily, and Germany, a new Holy Roman Empire was born, and Pope John XII agreed to crown Otto. Second, the pope also agreed that any pope-elect would pledge allegiance to the crown, effectively putting crown ahead of mitre. This would reverberate through history for a long time.

Otto and his successors began the practice of filling clerical appointments with their own friends and family, creating the title of “prince bishop”. As the educated class of Germany, they became the administrators of the government. However, as a religious faction, they were more closely tied to German royalty than to the Pope.

Ottonian Kings and popes argued about who had authority to appoint and approve bishops and emperors for decades. The contest became known as the “Investiture Controversy”. It prompted Pope Gregory VII to proclaim: “1) The Roman Church has never erred, can never err, 2) the pope is supreme Judge, may be judged by none, and there is no appeal from him, 3) no synod may be called a general one without his order, 4) he may depose, transfer, reinstate bishops, 5) he alone is entitled to the homage of all princes, 6) he alone may depose an emperor.” Not much wiggle room in that one. Power and the Holy in the Age of the Investiture Conflict: A Brief History with Documents (Bedford Series in History & Culture)

The Ottonians lasted until 1024 CE. The nadir of sovereign/papal relations was Henry IV’s “penance at Canossa”. This was a momentous reign with more missteps than a soap opera. Check out Henry IV of Germany 1056-1106.

So, when the son of Henry IV, (wait for it… Henry V!), perished without an heir, the Archbishops jumped in to ensure the next emperor had a proper deference for the Church. A succession struggle (read “war”) ensued. This boomeranged badly on the Church as the House of Hohenstaufen took charge amid a decade of civil war. This struggle involved the Welfs and Waiblingers, known in Italy as the Guelfs and Ghibellines.

The disastrous Second Crusade to Jerusalem took place around this time, 1145-49. When the German King Conrad III returned from the Middle East, Germany was in chaos. It was another stage set for a hero. Up stepped Frederick Barbarossa (“Red Beard”), also known as “The Great,” of course, in 1152.

While Frederick clearly liked the sound of “Holy Roman Emperor”, he wrestled with various popes for supremacy, just like the Ottonians. The Hohenstaufen Dynasty lasted over a hundred years, during which the emperors and popes battled endlessly. Armies marched back and forth between Germany, Lombardy (northern Italy), the Papal States (central Italy), and Southern Italy and Sicily. Popes were named and deposed. Emperors were excommunicated, sometimes multiple times. Crusades took place with or without papal consent. It was a time of enormous egos and intrigue. The Deeds of Frederick Barbarossa (Records of Western Civilization Series), and Frederick Barbarossa: The Prince and the Myth

.

By 1254, The Holy Roman Empire was irrevocably split between Germany and Southern Italy. The struggles with the popes, which brought France, Britain, and Spain into the various conflicts, wore out the Hohenstaufens after Frederick II died in 1250. Germany dissolved into two decades of pandemonium, called the “Great Interregnum”. Every major and minor German noble and prince bishop jealously clung to their own patch of sovereignty. The emperor was elected by seven electors, which pitted the Roman Catholic Rhineland states against the secular eastern states.

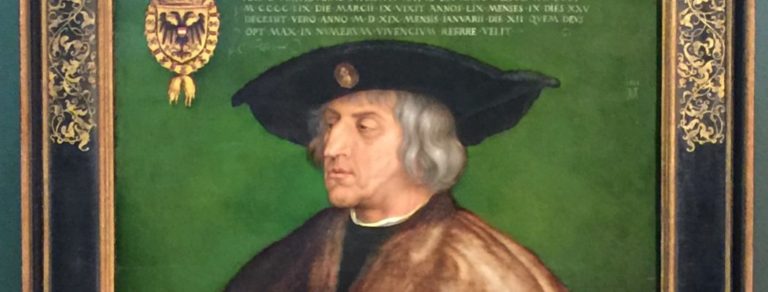

When they elected Rudolph I of the House of Hapsburg, in 1273, he was far more intent on consolidating a base for his own dynasty than with any worry about the larger empire. Rudolph swept into Austria in 1276, but renounced all claims for southern Italy and the Papal states.

By 1338, the electors declared they had no need for papal intervention in their elections. Divorce with the Church was complete. The reputation of the Papacy was at an all-time low in Germany. The seeds of the Protestant Reformation would take two hundred years to flower. But, they had definitely been planted.