For three hundred years, from 1000 to 1300 CE, despite incessant warfare, the population of Europe doubled. In three short years, from 1348-1350 CE, it went all the way back down again. Increased traffic along the Silk Road from China to Europe, exemplified by the remarkable odyssey of Marco Polo, from 1271-1295 CE, brought great wealth to some and alarming devastation to many. The Travels of Marco Polo: Edited by Peter Harris (Everyman’s Library Classics & Contemporary Classics)

The Black Death arrived with rats on ships from Asia and the disease spread from Italy northward. Estimates suggest that southern European areas lost as much as 70% of their population. Even large cities in Germany are thought to have lost 60% of their people. This contributed to the disruption of the constant political and ecclesiastical bickering of the time. A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century, and The Black Death: The Great Mortality of 1348-1350: A Brief History with Documents (The Bedford Series in History and Culture)

By 1356, the Holy Roman Empire was neither holy nor Roman. However, the name persisted and a new structure for electing the emperor was announced in the Golden Bull. Seven electors were designated to include: the Archbishops of Mainz, Trier, and Cologne, Count Palatine of the Rhine, the Duke of Saxony, the Margrave of Brandenburg, and the King of Bohemia. The scheme lasted for the next four hundred years and calcified the fractured political landscape of Germanic Europe.

Popes, kings, dukes, and princes with a claim of sovereignty were pretty much at war for the next hundred years. In 1438, Albert II of the Hapsburgs was elected King of Germany. The subsequent rise of the Hapsburgs is a tale of the judicious wielding of marriage bouquets and political leverage.

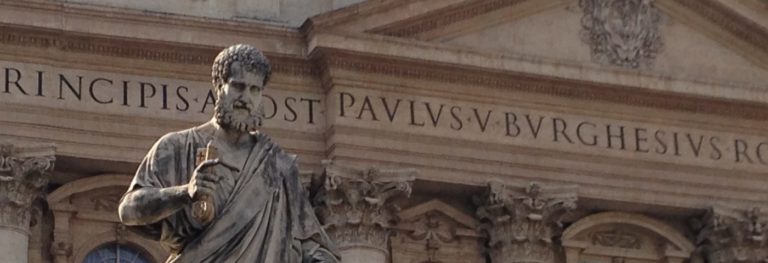

The Hapsburgs were from Austria, which was a strategic crossroads between Germany and Italy. Albert II married into the Hungary succession, and the two countries would be inseparable for centuries. His successor, Frederick III, outlived most of his antagonists and then outlasted Charles the Bold of Burgundy, finagling Charles’ daughter, Mary, as a bride to Frederick’s son, Maximilian I, (shown above), who assumed the Emperor’s crown in 1493.

Mary’s dowry included the French Burgundian lands and a sizable piece of the Netherlands and Flanders. This gave rise to the dynastic motto: “Let others wage wars, but you, happy Austria, shall marry”. Germany and the Holy Roman Empire: Volume I: Maximilian I to the Peace of Westphalia, 1493-1648 (Oxford History of Early Modern Europe)

Maximilian was forced to negotiate away the Burgundy region. But, he made up for it by marrying his son, Philip the Handsome, to Joanna, daughter of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Aragon and Castile. Doing so, he acquired Spain, Naples and Spanish America for their son, Charles V. Max got Chuck elected Holy Roman Emperor in 1519 by means of substantial bribery. He, then, proceeded to marry two granddaughters to secure the Hapsburg hegemony over Hungary and scrappy Bohemia. Emperor Maximilian I and the Age of Durer

This was a time of the renaissance and the age of great monarchs. Some of the most influential at this turning point in European and religious history are described in Four Princes: Henry VIII, Francis I, Charles V, Suleiman the Magnificent and the Obsessions that Forged Modern Europe.

It may be recalled that Ferdinand and Isabella, besides bankrolling Columbus and raking in the blood-stained, golden dividends of South America, were the perpetrators of the Spanish Inquisition. They were, therefore, intensely Catholic. Their grandson, Charles V, showed up as Holy Roman Emperor, defender of the faith, just in time for Martin Luther’s Reformation. The story of the Reformation, and the 130 years of wars that finally ended in 1648, is told in the article, “Sweden’s Fifteen Minutes of fame” in the Baltic Cruise section. See also The Thirty Years War: Europe’s Tragedy

As the ink dried on the multitude of treaties required to mop up the Protestant wars, The Hapsburgs were still the Holy Roman Emperors. However, a major power was gathering like a storm up north. The Hohenzollerns of Prussia and Brandenburg would challenge the Hapsburgs for the next two centuries.

If there ever were such a people as the “indigenous Prussians” on the Baltic coast, there are very few of them left today. In 1230 CE, their Polish overlord identified them as pagans, invited the Teutonic Knights to deal with them and, poof, no more pagans.

The history of the Order of the Teutonic Knights is one of efficiency and brutality. Check out TEUTONIC KNIGHTS They were very good at their own public relations among European capitals, using their papal connections to excellent advantage while they built their own kingdom. Ultimately, they became too big for their Polish and Lithuanian neighbors who trounced them in 1410. Western Prussia was lost to Poland in 1466 CE. Two historical novels with a wealth of background on the Knights versus Poland episodes, both sympathetic to the Polish, include The Teutonic Knights

, by polish author, Henrik Sienkiewicz, and Poland

, by James Michener.

In 1618, through marriage, the Margrave of Brandenburg (Berlin) became Duke of what was left of Prussia, creating the state of Brandenburg-Prussia. He was a Hohenzollern, and the new state would have a big impact on European history for the next three hundred years. Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600-1947

Times were tough, particularly during the Thirty Years’ War, as the Swedes swept through on their way to saving Protestantism. Duke Frederick William I took charge and, noting the effectiveness of the Swedish military machine, reorganized his own forces and created a standing army.

The Duke’s son, not content to oversee a Duchy, crowned himself Frederick I, King of Prussia, in 1701 CE. He and his son, King Frederick William I, (not to be confused with the aforesaid Duke), strengthened Prussia while Europe struggled with succession issues in Spain, Poland and the Holy Roman Empire.

In 1740 CE, Frederick II “the Great” took over Prussia and Maria-Theresa, the controversial female heiress, took over the Hapsburg dominions, including the title of Holy Roman Empress. She lasted 40 years. Frederick lasted 46 years. They battled and connived against each other the whole time. Frederick the Great (New York Review Books Classics), and Frederick the Great: The Magnificent Enigma

, and Maria Theresa of Austria: Full-Blooded Politician, Devoted Wife and Mother-to-All

.

The prize was the coal rich lands in Silesia, in the southwest corner of modern-day Poland. It was an enormous source of wealth. In 1740, it belonged to Austria. After three separate wars, culminating in the world war known as the Seven Years’ War, 1756-1763, Prussia managed to retain Silesia while the political map of the world was redrawn.

This was a time of absolute monarchies whose armies and constant warfare reflected the complete disregard of the royalty for the lives of their countrymen. It inspired British Prime Minister William Pitt to remark, “Unlimited power is apt to corrupt the minds of those who possess it.” Liberal philosophies were gathering strength that would set haves and have-nots at odds for the next 150 years. It would not be a comfortable transition.