The reigning British monarch, Elizabeth II, is such a paragon of impeccable propriety it is hard to imagine that some of her predecessors were unstintingly ruthless. Ever since William the Conqueror built the Tower of London, it has been witness to many a tale of sovereign shenanigans. Henry VIII beheaded two wives there. His daughters, “Bloody Mary” and “The Virgin Queen” Elizabeth I, managed a number of insubordinate disagreements with the executioner’s axe.

But when the British are called upon to name the worst of the worst among their nobility, the dubious honor almost always goes to Richard III. Right out of central casting as the evil, hunchbacked uncle, (think: “Scar” from the Lion King), Richard, Duke of Gloucester, saw his one slim chance for glory and proceeded to bludgeon it to a bloody pulp. The story and its most prominent controversy are the subject of The Princes in the Tower

, by British historian, Alison Weir.

The British Plantagenets, founded by Henry II, (See the Academy Award winning “The Lion in Winter”), battled unsuccessfully with France’s House of Valois in the Hundred Year’s War, 1337-1453, basically bankrupting England. What was left of the Plantagenets split into the houses of Lancaster and York and proceeded to spend the next three decades, 1455-1487, fighting the War of the Roses over the English throne.

The Yorkist champion was Edward IV, who won his crown in battle and managed to keep it in the same manner. Though seen as charismatic and able, he couldn’t stop fighting Lancastrians and the French. This led to ill health and he passed away in 1483. His wife, Elizabeth, was seen as a bit of a gold-digger and was not particularly popular, even among her husband’s supporters. His two young sons, aged 12 and 10, were presumably the heirs to the throne. On his deathbed, Edward IV named his trustworthy brother, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, as the Protector for the crown princes. What could go wrong?

Having been handed the keys to the Kingdom, Richard did what every frustrated “next in line” royal brother always did: he usurped the throne. To “protect” the boys, he lodged them firmly under lock and key in the Tower. Then, by artful explication and persuasion, he managed to get Edward’s marriage to Elizabeth declared invalid. That meant the boys were…(Would you look at that!)…illegitimate! And if the boys were not fit to sit on the throne, why, then, Richard would just have to reluctantly assume the heavy responsibilities of the realm. He basically crowned himself Richard III.

The two young boys, Edward and Richard, were never seen again. Ever. Sometime between 1483 and 1486, they vanished. All England assumed Richard III had ordered them eliminated to remove any challenge to his rule. It was never proven that he ordered the killings and the evidence was either ignored or went to the grave with its perpetrators. In 1674, workmen unearthed a coffin with two young male skeletons from underneath the White Tower staircase. Weir presents all the evidence available to conclude the princes had been murdered at the command of their uncle.

With so much questionable activity, the Kingdom was restless during Richard’s short reign. Everyone assumed he had committed atrocities, but so had prior monarchs. No one was about to stand up and accuse the king of murder. The only recourse was rebellion. So, the last of the Lancastrians rebelled and Richard III fell in battle in 1487, ending the War of the Roses and sprouting the House of Tudor.

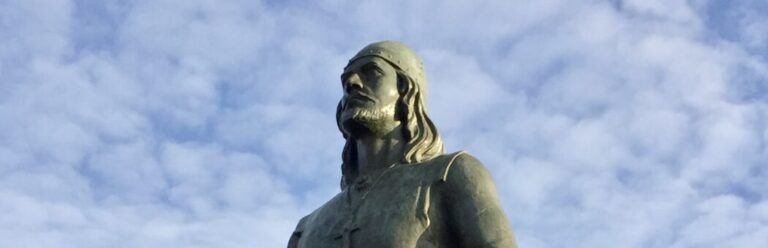

The legacy of Richard III as dastardly and evil was cemented in spectacular fashion by William Shakespeare, whose play, “The Life and Death of King Richard III,” takes its namesake to task with some of Shakespeare’s worst epithets. In one of life’s funny ironies, the unmarked grave of Richard III was discovered by historians in 2012. They could tell it was him by the curved spine. Afflicted with scoliosis, he really was a hunchback. He was reburied in 2015 in a muted celebration in Leicester, near the battlefield on which he met his demise.

The story of The Princes in the Tower details the significant transition between two of England’s most historic dynasties. Full of blood, betrayal, and brutality, it provides a vivid account of the excesses of corrupt power.